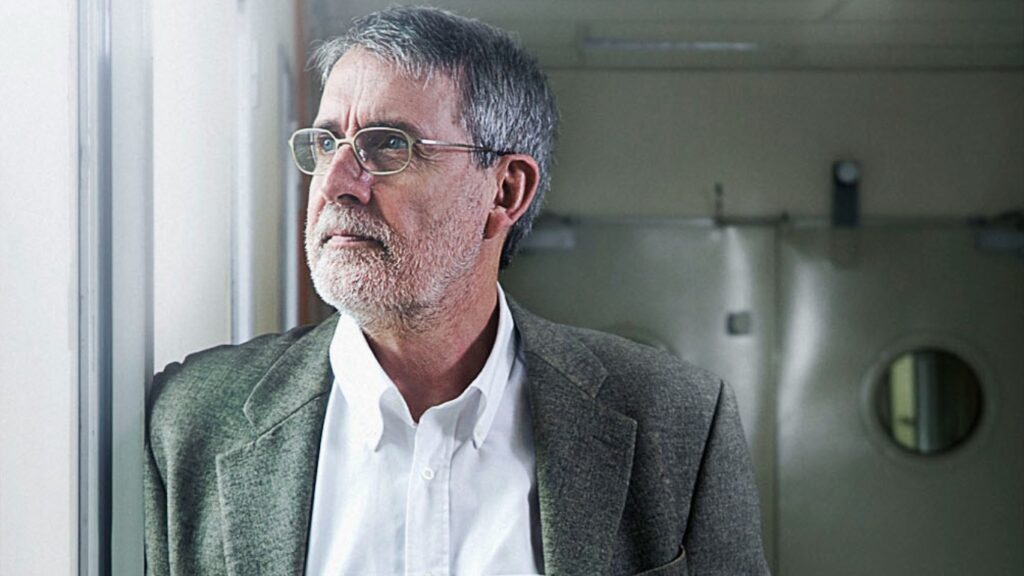

Doctor and researcher Xavier Bosch has been selected this year as the winner of the the International Papillomavirus Society‘s Maurice Hilleman Award. The award, announced on 19 November, acknowledges the professional career and contribution to the development and promotion of the vaccines against this kind of virus.

Bosch, principal investigator at the Bellvitge Biomedical Research Institute (IDIBELL), emeritus researcher at the Catalan Institute of Oncology (ICO) and member of the Faculty of Health Sciences of the Universitat Oberta de Catalunya (UOC), was instrumental in identifying the human papillomavirus (HPV) as responsible for cervical and other cancers, which was the necessary starting point to develop the vaccines. He has also participated in studies on its effectiveness and is actively involved in promoting its use.

“This prize is awarded by colleagues who are experts in the field and I receive it with much gratitude,” said Bosch, “but although it’s awarded in a personal capacity, this has been possible due to the dedication of the teams I have worked with. The most important thing is to collaborate with a good team, manage them and keep them together.”

Hilleman and key research on the virus

The award is named after the American vaccinologist Maurice Hilleman. Known as an “unsung hero”, he contributed to the development of several dozen vaccines, including 8 of the 14 vaccines commonly included in vaccination schedules. One of the latest to be introduced in some countries has been the papilloma vaccine, which contributes primarily to the prevention of cervical cancer – and Bosch helped establish this link.

In the 1980s it was known that there was a link between the number of sexual partners and the risk of developing cervical cancer, but the cause was unknown. The main suspect at the time was not the papillomavirus, but a herpes-like virus. During that decade, Bosch’s team followed in the footsteps of the group led by professor Zur Hausen in Heidelberg, Germany, who suspected that the culprit might be the former, and updated viral DNA detection techniques to include them in population-based epidemiological studies.

The Centre International de Recherche sur le Cancer (CIRC) in Lyon, France, first, and then the Catalan Institute of Oncology organized studies that were extended to more than 30 countries and included over 25,000 cases. Case designs and controls compared women with and without cancer. They looked for markers of exposure to the virus and calculated the increased risk of cancer in women exposed to the infection.

“We were among the first to use the technology to detect HPV in studies of this kind,” said Bosch. The link was so strong that a causal relationship between the virus and the development of cervical cancer was established with certainty. Although in the vast majority of cases HPV infection does not cause clinical changes or symptoms, virtually 100% of women who develop cervical cancer have previously been infected with HPV. It was later confirmed that HPV is also related to other types of tumours of the male and female genital tract, as well as in about half of the tumours found in the oropharynx.

Confirmation of the viral origin of cervical cancer was the initial step in deciding to develop a vaccine, the first of which appeared in 2006. It also served to update screening programmes by incorporating viral detection into population-based prevention protocols.

A safe and effective vaccine

Today, more than 120 million people have been vaccinated against HPV worldwide. “Some isolated voices tried to raise doubts about the vaccine,” Bosch explained, “but the truth is that it’s a very good vaccine against the major HPV types and an attempt is even being made to apply the technology to other more difficult viruses, such as HIV or influenza”. Specifically, according to Bosch, “the latest studies tell us that it provides about 90% protection against infection and against the development of cancer. And it is safe. With so many millions of people vaccinated, there have been no warning signs.”

In Spain, it is part of the vaccination schedules and is routinely administered to girls from the age of 12. Its effectiveness in the population will be seen over time. Today, it is estimated that 10%-12% of women in Spain are infected with the virus and that it causes 2,000 tumours a year and 800 deaths. In developing countries the problem is much worse, with figures at around 30% of women infected.

However, it is a potentially eradicable virus. This has been stated by the World Health Organization, which advocates a mass vaccination strategy in combination with appropriate screening strategies. Bosch shares this opinion: “the models prove that, although complicated, eradicating the virus worldwide is possible”.

To achieve this, he thinks it is vital to make efforts in education and promotion. Along with the lines of research that he is still working on, Bosch carries out “a lot of training for doctors and health personnel and for professionals who are in contact with patients, so they know that the vaccine exists, that it is necessary, effective and safe. The main objective now is to increase vaccine coverage and make it accessible to the least developed countries.”