Humans can learn effectively, especially when they are externally rewarded (for example, with money or desirable incentives after their actions). Instead of externally-triggered learning (carrot-based learning), self-organised or intrinsically driven learning refers to those learning processes without any objective reward. If you think of it, humans are often involved in these types of rewardless learning activities (think on the amount of time most of use spent solving crosswords, solving interesting problems, learning while playing or even learning new languages, etc.).

An intriguing question is how these self-determined learning activities are triggered, sustained and maintained.

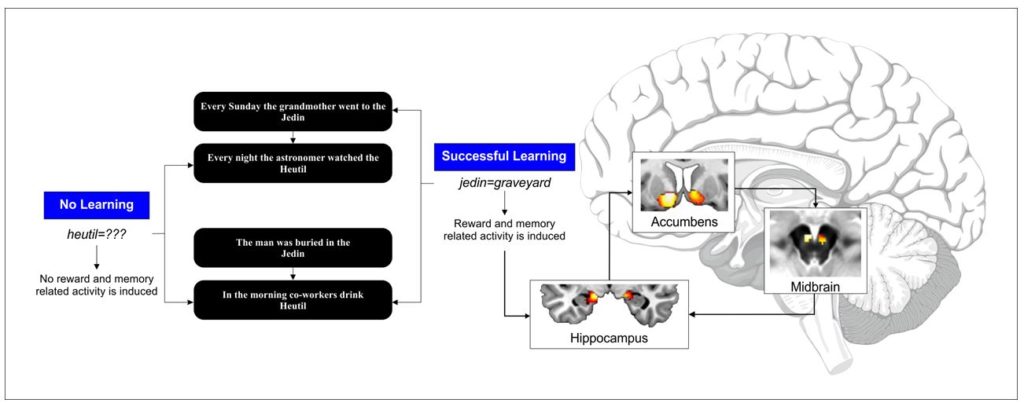

An international team of scientists from Bellvitge Biomedical Research Institute (IDIBELL) and the University of Barcelona (Cognition and Brain Plasticity group, IDIBELL-UB) and Magdeburg University (Department of Biological Psychology) has shown in its latest research work, published in eLife, that this internal-driven learning process utilizes a network of brain regions very similar to the one triggered by external, incentive-driven learning. During self-organised learning the brain also triggers the reward system to broadcast a “reward-pleasure” signal. This reward signal highlights the importance of the ongoing (learning) process, links the reward- with the memory-system and boosts memory formation. The involvement of the reward system also triggered subjective enjoyment: participants’ pleasantness ratings during learning were highest for those learning items which they correctly remembered even after a week.

“Previous research showed that the brain’s memory structures communicate with reward regions if an external reward is given during learning, for instance with money. But, in our daily life we often learn without being rewarded. In our study we set out to identify the brain regions linked to learning without explicit reward” says senior author Professor Toemme Noesselt (Institute of Biological Psychology, OVGU, Magdeburg). “Surprisingly, we found the same areas involved in external reward processing, were also active during internally driven learning. This suggests that the brain can simulate the occurrence of an external reward.”

The researchers scanned the brains of 36 volunteers using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). Participants read pairs of sentences which contained new words while being scanned. Half of the paired sentences provided a congruent meaning for the new word. The volunteers were asked to acquire the meaning of the new words, on their own, without any external help. The activity of the brain’s reward-memory loop did indeed increase whenever a volunteer learned the meaning of a new word.

“We then tested whether the activity of this loop is linked to longer-lasting memory traces,” explains lead author Dr. Pablo Ripollés (Cognition and Brain Plasticity Unit, IDIBELLUB). “Indeed, we found that the activity of the reward-memory loop is highest for words still remembered after one hour. In two follow-up experiments we also showed that the participants’ pleasantness ratings during learning were highest for those new words which they correctly remembered even after a week. In accordance, skin conductance responses, a marker of emotional processing, were also highest for remembered words. All our evidence points at a crucial involvement of intrinsically triggered reward related processes during internally driven learning.”

“External rewards and feedback like grades are common educational strategies. We can only speculate as to how this internal mechanism reacts if confronted with external signals”, adds Co-Senior Author Prof. Antoni Rodriguez, (ICREA, IDIBELL, UB) “A key question for the future is to identify the circumstances during which internally driven learning is more effective than relying on external feedback and incentives. This will tell us how internally driven learning can be used to improve educational programs –

for instance second language acquisition – and rehabilitation programs – for instance, the recovery of verbal skills lost after stroke”.