A team from the Faculty of Psychology of the University of Barcelona (UB), the Institute of Neurosciences of the UB (UBNeuro) and the Bellvitge Biomedical Research Institute (IDIBELL) has identified for the first time in humans, and in a realistic environment, a key neurophysiological mechanism in memory formation: brain waves type Ripple, high-frequency electrical oscillations, which act as markers that delimit and organize the different episodes or fragments of information that the brain will remember in the future. These findings, published in the journal Nature Communications, deepen the understanding of how memory is organized in the human brain and open new avenues to address disorders related to memory impairment.

The research is led by Lluís Fuentemilla, researcher in the Cognition and Brain Plasticity Group of IDIBELL and UBNeuro, and is part of the doctoral thesis carried out in this same group by Marta Silva, first author of the article and currently at Columbia University (United States). Experts from the Epilepsy Unit of the Hospital Clínic de Barcelona, Columbia University, the Ruhr University Bochum and the University of Munich (Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität – LMU) (Germany) have also collaborated.

The memory of specific episodes is the basis of memory

Even though the experience is constant, there is a lot of evidence that the brain segments it when there are changes in the flow of information to convert it into memories. “These segments mark that, from a given moment, the brain closes an episode in memory and begins to register another. For example, when you are doing something and you receive a phone call or the doorbell rings, the brain identifies that there has been a change in the course of the experience and uses these events as if they were a punctuation mark, a period and apart in a sentence, to proceed with the storage of what you were doing in the form of an episode.” explains Lluís Fuentemilla.

Previous studies in mice have indicated that ripple-like waves play a fundamental role in the formation of memories. “These waves are thought to coordinate the transfer of information between the hippocampus and neocortical regions — to the temporal and frontal cortex — facilitating the integration of new memories. This neural signal is key to generating synaptic potentiation, allowing the brain to fix and consolidate a memory,” the researchers explain.

A pioneering experiment

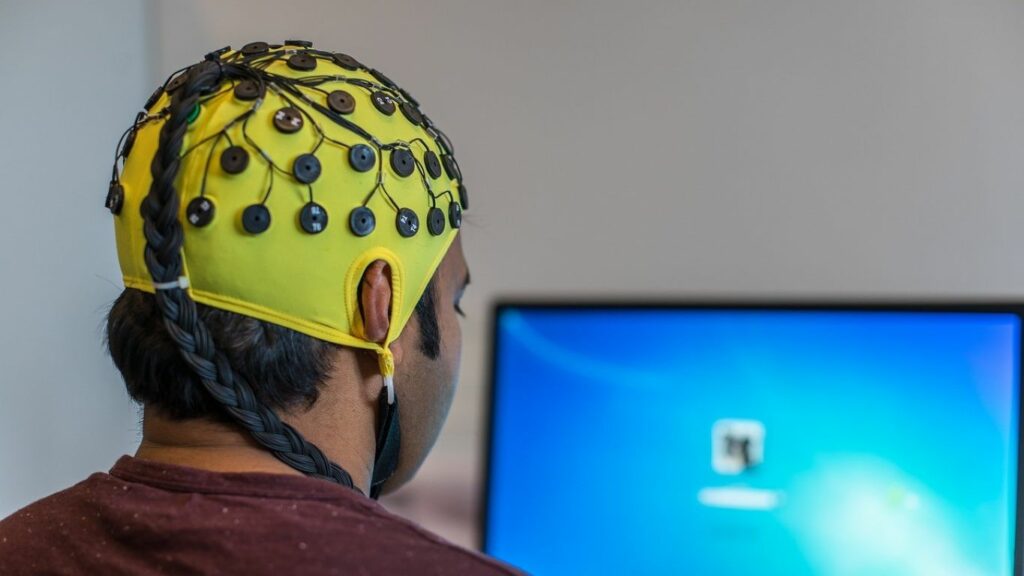

Although these signals have been studied extensively in animals, especially mice, their analysis in humans has been very limited. This is due to the difficulty of recording them, since they originate in brain areas that require the use of intracranial electrodes. In this study, however, the researchers have managed to analyze these waves in a naturalistic context, that is, in conditions close to everyday life. To do this, they recorded the intracranial electrophysiological activity of ten patients with epilepsy – operated on for clinical reasons – while watching the first episode of the BBC series Sherlock, with a duration of 50 minutes. “This type of narrative format, as in real life, presents scene changes that the brain identifies as event boundaries. Subsequently, the participants were asked to recall and relate what they remembered of the plot,” the authors detail.

The results showed a dynamic pattern of activation of ripple waves during the encoding of memories. “We observed that these waves were produced both in the hippocampus and in the neocortical areas. However, they followed a differentiated temporal rhythm: in the hippocampus, ripple activity increased at event boundaries, reflecting their role in segmentation; on the other hand, in cortical regions, their presence was higher during the internal development of events,” explains Marta Silva.

According to the researchers, this pattern suggests coordination between the two brain structures as if it were “an orchestra”: neocortical regions actively process information and the hippocampus springs into action when a scene change occurs to “package and consolidate” the memory.

Segment to remember

These findings reinforce the idea of the importance of segmentation and structuring in the formation of memory. “What we see, both in this study and in related works, is that it is not enough to pay attention and record information, but it is equally or more relevant to organize it in the context of the constant flow of information. In other words, it is not only about activating the brain machinery while it is recording information, but it also has to act as an orchestra conductor that marks when the memory begins and ends. These signals help not only to ensure that there is a record while it is happening, but also to organize the information in a coherent way,” they highlight.

The results could also have important implications for the understanding of memory disorders and for the development of future therapeutic interventions. “Until now, when faced with an amnesic problem, we used to think of attention deficits or difficulties in acquiring information. Our results suggest that there could also be a failure in these segmentation signals, in how information is structured in the brain,” they argue.

In this sense, the research opens the door to exploring therapies that consider the way in which information is organized at the brain level. “In older people, for example, who begin to show memory impairment, it could be beneficial to present information in a more structured way, with clear pauses between relevant events. Not only because of a matter of cognitive rhythm, but because that could facilitate its correct encoding and storage,” they conclude.

The Bellvitge Biomedical Research Institute (IDIBELL) is a research centre created in 2004 specialising in cancer, neuroscience, translational medicine and regenerative medicine. It has a team of more than 1,500 professionals who, from the 73 research groups, generate more than 1,400 scientific articles per year. IDIBELL is owned by the Bellvitge University Hospital and the Viladecans Hospital of the Catalan Institute of Health, the Catalan Institute of Oncology, the University of Barcelona and the City Council of L’Hospitalet de Llobregat.

IDIBELL is a member of the Campus of International Excellence of the University of Barcelona HUBc and is part of the CERCA institution of the Generalitat de Catalunya. In 2009 it became one of the first five Spanish research centres accredited as a health research institute by the Carlos III Health Institute. In addition, it is part of the “HR Excellence in Research” program of the European Union and is a member of EATRIS and REGIC. Since 2018, IDIBELL has been an Accredited Centre of the AECC Scientific Foundation (FCAECC).